3blue1brown recently felt the need to add a supplementary video to its Grover’s algorithm introduction. Apparently, a lot of people have been confused by what I believe is basically just the logical structure of the concept, or why this algorithm is interesting and surprising in the first place.

For someone who only knows about classical computing and a little about algorithm complexity, the simplest way to get an intuition about Grover’s algorithm might be to first consider this:

Imagine that you have a list of N random numbers, that is not sorted:

[73, 18, 92, 45, 6, 59, 31, 84, 12, 67, …]

What is the fastest way you can find a given number in such a list?

The answer is clear: you need to go through every item sequentially,

there’s no shortcut, meaning that it’s fundamentally O(N). When you

think about it, it intuitively makes sense, almost in a physical way

also. For such a simple problem, if you could do better, what would it

even look like in the first place? But it turns out that with Grover

and the power of quantum computing, you can do better: O(sqrt(N))!

To someone with even a rudimentary understanding of algorithms, this

should be surprising in the same sense as learning that you can sort a

list in O(N log N), even though it’s more intuitive to think it

takes O(N^2).

So more generally, why wasn’t this basic intuition simply presented in the otherwise fantastic video?

I believe it’s because mathematicians, in general, are very reluctant to explain things in a way that could be considered a betrayal of the rigor and generality of mathematics.

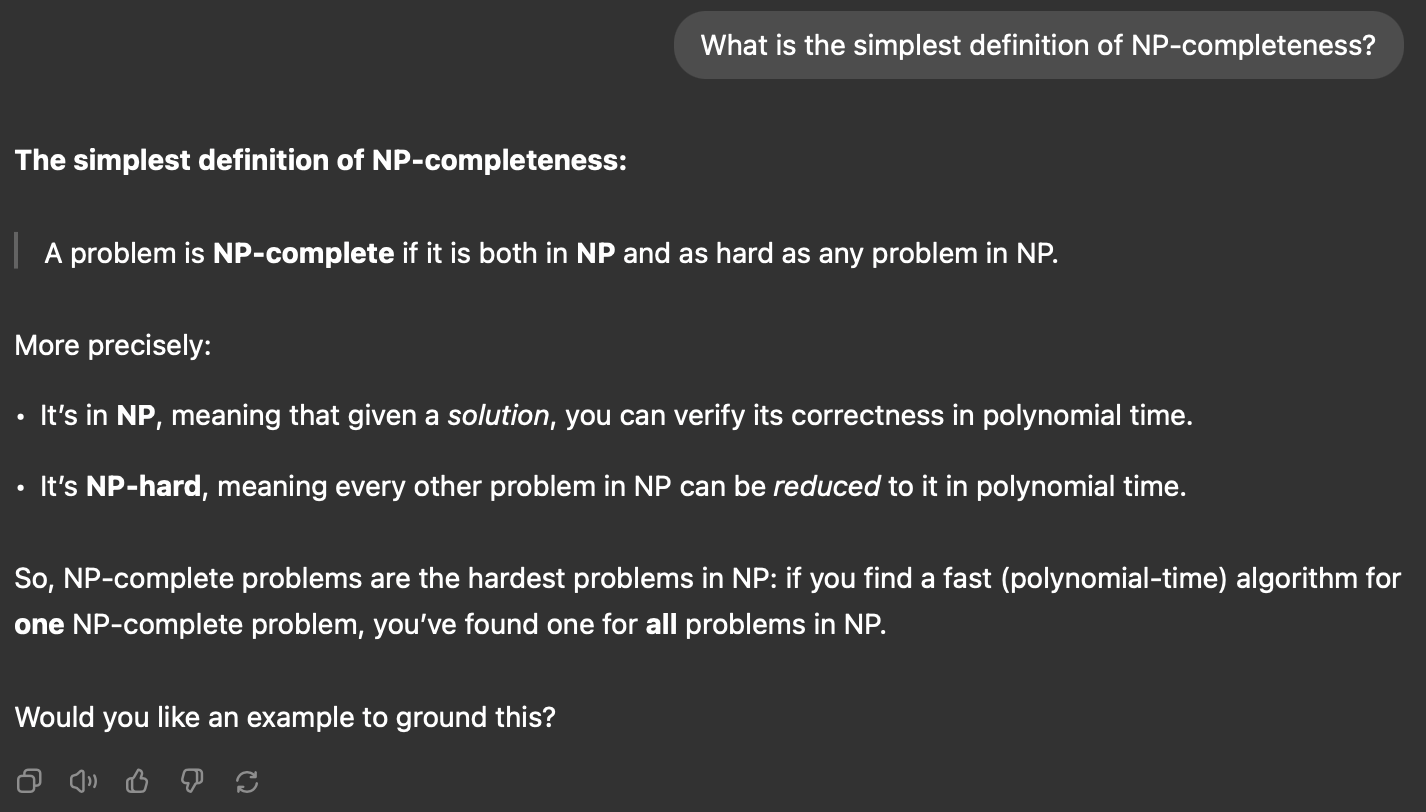

Consider the definition of NP-completeness for instance:

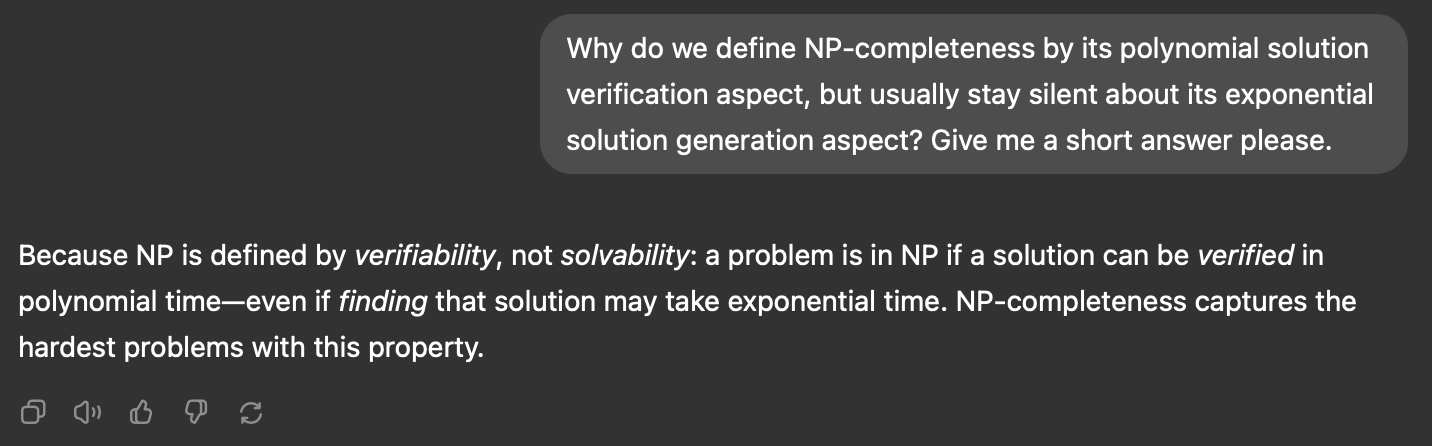

I’ve always wondered why the definition of NP-completeness seems to miss a critical element, one that I’m certain is part of the mental representation of almost anyone who ever interacted with that concept: NP-complete problems take exponential time to solve!

That’s it — the reason is that we want to keep things rigorous and general, I get it. But sometimes the cost is a harder mental representation, which can hamper students’ intuition for a very long time. My opinion would be that sometimes it’s better to sacrifice a bit of rigor in order to be more blunt about what is surprising about a mathematical idea.